The agriculture system is unique because it is deeply intertwined with so many other systems – food, finance, climate, policy – and at each level of society: local, regional, national and global. As a result, the way we operate agricultural systems can have unintended consequences far beyond the system itself. The global industrial food system, built over the past 5+ decades is a prime example of this. This system is characterized by extraction and degradation. It starts with the soil on the farm, but the implications reach far beyond.

Soil Degradation and What It Means for Everyone

Productive land and fertile soil are our most significant non-renewable resource. However today, 33% of the Earth’s soils are already degraded and over 90% could become degraded by 2050, according to the FAO. Each year, an estimated 24 billion tons of fertile soil are lost due to erosion – that’s 3.4 tons lost every year for every person on the planet.

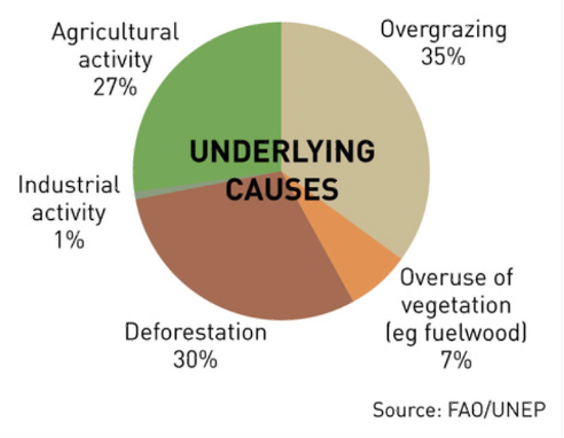

These trends are caused in part by the way we farm. Agriculture and overgrazing account for more than half of the major causes of soil degradation, according to the FAO.

Major Causes of Soil Degradation

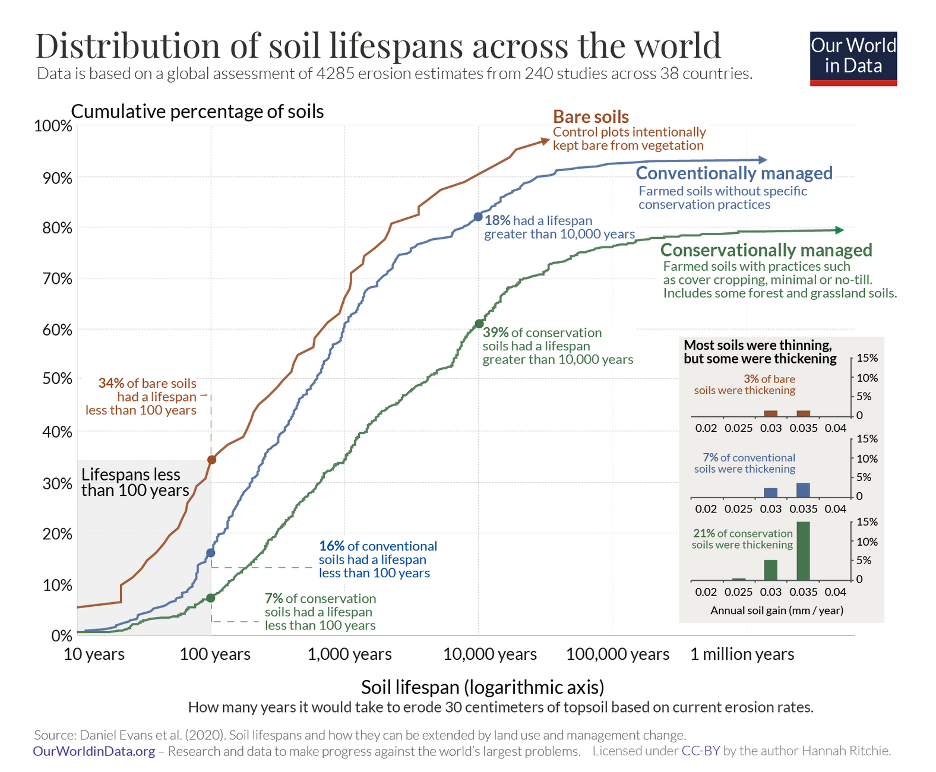

Agricultural activities, such as excessive tillage, heavy use of machinery, the use of chemical inputs, depletion of soil organic matter, and decreased on-farm biodiversity, can lead to degraded soils. As a result, the soil can experience structural deterioration, reduced water retention and availability, and toxic salt levels. This degradation ultimately has repercussions for farm operations in terms of soil health, productivity, and on-farm resilience in the face of increasing weather and climate events. The way that soils are managed may determine their life spans and ability to support farming altogether, according to the data below by Our World in Data.

But soil degradation is just the beginning of the story. Industrial agriculture, and the practices associated with it have far reaching implications for each and every human on earth, such as:

- Approximately 25-35% of global Green House Gas emissions are attributable to food systems and 71% of these emissions come from agriculture production and land use.

- The global food system is the primary driver of biodiversity loss – with agriculture identified as a threat to 86% of species at risk of extinction.

- Food is getting less healthy with research showing that key vitamins in some fruit and vegetables have declined by 20-50% over the past 60 years, which can be attributed to the industrial practices, including “chaotic mineral nutrient application, the preference for less nutritious cultivars/crops, the use of high-yielding varieties, and agronomic issues associated with a shift from natural farming to chemical farming.”

Each of the above has real societal costs – such as increased climate risk, disease, healthcare costs, and more – that are rarely taken into account when making decisions across the food system – from farmer to consumer and from policy maker to investor.

Investing in Regenerative as a Soil Health Solution

Regenerative practices on the farm that nurture and build soil health – such as cover cropping, no- or low-till farming, crop rotation, eliminating chemical inputs, and composting, among many others – hold a tremendous amount of potential to address many of these challenges presented by industrial agriculture productions systems. For example:

- Healthy soils act as a carbon sink, meaning they absorb and store carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Practices such as cover cropping, no-till farming, and crop rotation enhance soil organic matter content, which increases the soil’s ability to sequester carbon.

- Reduced tillage also decreases soil disturbance, which in turn reduces the release of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases into the atmosphere.

- The use of chemical inputs as pesticides, herbicides, and fertilizers can be harmful to soil biology and structure. Reducing or eliminating chemical inputs can improve nutrient cycling, soil structure, and overall soil health, while reducing soil erosion.

- Soil health practices such as buffer strips and riparian zones can also help prevent soil erosion and nutrient runoff into water bodies. This not only improves water quality but also contributes to mitigating climate change by preserving the carbon stored in soils from being washed away.

- Practices such as mulching and agroforestry improve soil structure, water retention, and nutrient cycling, making ecosystems more resilient to extreme weather events, such as droughts and floods.

- Building soil health can also improve crop nutrient density by enhancing nutrient availability, increasing nutrient absorption, and minimizing nutrient leaching.

Beyond all these agronomic benefits, regenerative practices can also lead to improved on-farm economics as a result of decreased input costs, premium pricing, and improved resilience. However, these improvements might take years to develop implement and do not come without a financial costs.

Capital As a Lever to Unlock Regeneration

The benefits of on-farm investment in soil health clearly have the potential to extend beyond the farm with positive impacts for society at large. However, the cost of adopting these practices is borne by the individual farmer. So within an agricultural system that was intentionally designed to maximize efficiency and output at the expense of the health of the underlying assets – soil – farmers are being asked to internalize the costs of doing something different, something that will also benefit the greater good.

There are an increasing number of farmers who are taking on this challenge of transition but many face barriers. Guidelight Strategies (funded by Patagonia) conducted a study on these barriers in 2020 and their findings still hold true today. Among the several obstacles to farmer adoption of practices that the report identified, the following stand out:

- Behavior and Cultural Change: The conventional way of farming is embedded in all the systems that farmers work in – cultural, operational, financial, and more. Moving outside of this paradigm can be difficult and risky.

- Trusted Technical Assistance: Farmers and ranchers are extraordinarily busy people, managing complex businesses in a risky, low-margin, and ever-changing business environment. Taking time to learn about and experiment with new management practices can be a slow and time-consuming process. Without technical assistance, many farmers do not have the resources, time, or energy to learn about, plan, implement, and monitor new practices on their own.

- Appropriate Markets: One of the potential incentives and benefits for producers of adopting new soil health practices is getting rewarded financially. This relies largely on premium end markets – if the markets don’t exist yet or the processing infrastructure to maintain the value of these products doesn’t exist, then the premium could be forfeited and the incentive to transition diminished.

- Financial Capital and Incentives: One of the biggest barriers to farmers actually adopting new soil health or regenerative approaches is the added costs and risks in changing any given practice. Even if they can ultimately lead to better economic outcomes – there is still initial risk during the process of the change, when transition costs are highest, and premiums are not yet attainable.

Listed together these barriers can seem daunting, and while there are no silver bullets, capital investment can play a significant role in addressing these barriers.

5 Ways to Invest in the Stewards of Our Soils

What we understand about the negative externalities of industrial systems, the benefits of transitioning to regenerative – including the economic benefits, and the barriers that farmers face in adoption, provides impetus for investment in those who steward our soil and land. Fortunately, there is a growing ecosystem of investment opportunities that allow for this. Here are 5 areas of investment that will support those who steward our soils:

Transition Finance:

The risks associated with on-farm practice and systems change can be daunting. Financial risk stands out because farmers often need to pay up front for inputs, equipment, and other costs that they won’t see an ROI on for multiple seasons. Specifically, for those transitioning to organic, there is a mandatory three-year transition period where they can’t collect an organic premium for their crop. Funders and investors that can support farmers during this period with grant or debt capital – with terms that take the temporal cycles of farming and transition into account – can unlock efforts to transition by reducing risk, costs, and stress. Even better, is when financing can be coupled with other tools needed for successful transition, like technical assistance.

There are an increasing number of organizations working to address this – Mad Capital’s Perennial Fund II, Steward, Agroforestry Partners and others – but still not nearly enough to meet increasing demand. So, an additional opportunity for investment is in those companies building new, innovative financial vehicles to support the transition.

Biological Inputs:

While the world of agtech can seem overwhelming and saturated at times, there is an important role that some technologies can play in enabling farmer transition to new practices and new systems. Biological inputs are designed to replace synthetic chemical inputs. While some question the regenerative nature of biologicals, they can be a valuable tool to support farmers to wean themselves off of detrimental pesticides, herbicides, and fertilizers. Moreover, adopted across large acreage, the ecological impact of transition to biological can be significant. Investment in the development of these tools has seen significant investment over the past decade and will likely remain relatively strong, although it will continue to get more sophisticated and nuanced. Another opportunity in this space may lie in helping farmers who are transitioning land to pay for biological inputs that can expedite and improve the transition process.

Enabling Data Technology:

Beyond biologicals, there is an entire suite of data technology solutions that are being built to enable the transition to regenerative agriculture by providing better market access and traceability. Aggregation technology, for example, that improves the ability of farmers and consumers to connect can facilitate access better prices. Platforms that enable food companies to better source regenerative ingredients can help build comfort and credibility for regenerative products and open more doors for farmers to find and secure offtakers. And traceability platforms that allow regeneratively produced products to maintain their value as they move through the supply chain can help ensure price premiums.

Emerging Brands with Regenerative Supply Chains:

Emerging food brands that source from producers committed to soil health practices and regenerative practices are a critical piece of the puzzle when it comes to expanding healthy farming systems. We can invest in transition and expansion at the farm level but if farmers don’t have an offtaker for their product, then they won’t be able to payback loans. Conversely, investments in emerging consumer brands – such as Simpli or White Leaf Provisions – to help them expand their capacity means these companies can now source more product from regenerative farmers.

For further examples of emerging brands check out this list on the Regen Brands website.

Consumer Education and Advocacy:

Building awareness amongst consumers about the connections between the way we do agriculture and the broader implications on climate, the environment, and human health has the potential to both increase demand for products that are grown regeneratively and to increase consumer willingness to pay more for these products. Moreover, there are an increasing number of efforts, like the Regenerate America campaign, going into educating policy makers about these benefits in an effort to change the course of policies that have historically dis-incentivized transition regenerative practices that may fall outside the industrial system.

An Obvious Opportunity

Equipped with an understanding of the benefits of regenerative farming and food systems – including the potential for positive economic outcomes – investment in this space appears to be a no-brainer. It can directly lead to improvements on the farm and for the climate, biodiversity, human nutrition and societal wellbeing, while serving diverse investment goals.

Beyond those described above, there is a multitude of other areas across the agriculture and food value chain that can help enable farmers to transform their operations and build regenerative outcomes on and off the farm. Where do you think the most promising opportunities lie? Let us know!

Sarah Day Levesque is Managing Director at RFSI & Editor of RFSI News. She can be reached here.

The content published by Regenerative Food Systems Investment (RFSI) is intended to be used for informational purposes only and should not be construed as legal, tax, investment, financial, or other advice.