The regenerative agriculture and food system is blossoming as an increasing number of farmers and food companies seek to transition to regenerative practices for the ecological, agronomic, climate, human health and economic benefits it can bring. Despite the rapidly growing engagement, the term “regenerative” itself still lacks legal definition. In some ways, this has been an intentional effort to not constrain growth of the space in its early stages. But the absence of a definition also creates barriers to understanding what regenerative actually is for consumers and other stakeholders, which may be detrimental. To counter these challenges, several regenerative certification programs have piloted in recent years, with even more launched in the past few months.

With these new initiatives, the buzz around how we define and label regeneration is growing louder. But what role are regenerative certifications playing in the development of the overall regenerative market – including decisions to invest in it – and is there such a thing as too many?

The Certification Value Proposition

Certifications in food and farming are designed to be universally recognized labels that communicate a production system and drive market growth through product differentiation and increased consumer understanding. Recent history paints a picture of the potential benefits certifications can bring to market expansion. Blake and Stephanie Alexandre of Alexandre Family Farms, a California dairy farm that holds several certifications including Certified Organic, suggest, “It’s instructive to look at the impact that Organic, Non-GMO and Gluten-Free (labels) have had on the number of products that have come to market and the increased number of agricultural acres devoted to those.” So, let’s take a quick look.

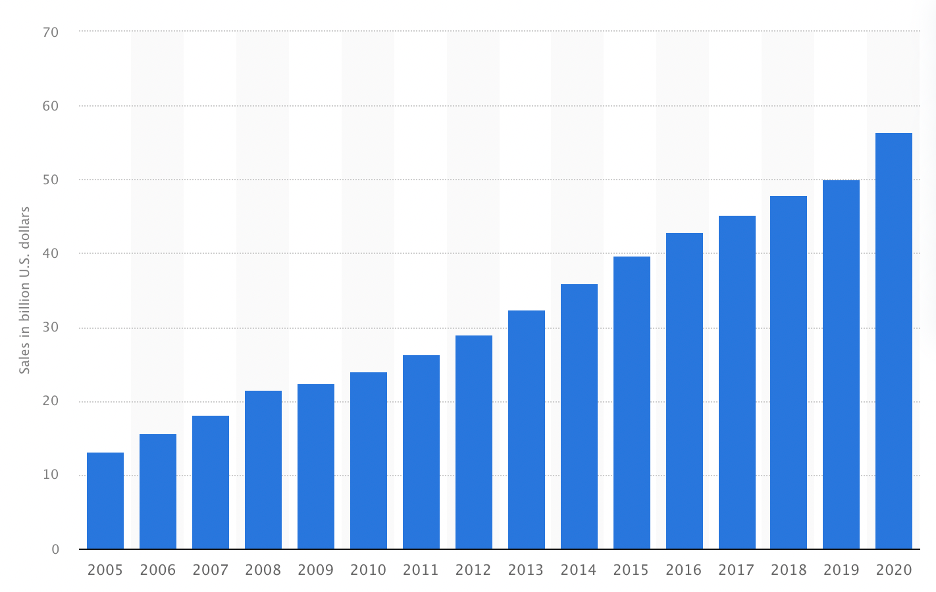

The USDA Certified Organic label was established with the national organic standard in 2000 and forbids the use of GMOs and most synthetic fertilizers. As the only federally regulated certification, it continues to serve as the go-to label to differentiate a crop or product in the market as ecologically produced. Since the inception of the label two decades ago, the organic market has grown significantly to about USD 56.5 billion in 2020. In addition, U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS) 2019 Organic Survey reports a 17% increase in certified organic farms and a 9% increase in certified organic acres since 2016.

Organic Food Sales in The United States, 2005-2020 (in billions U.S. dollars)

Similarly, the Alexandre’s explain that in 2004, the first GF (gluten free) seal came out to help celiacs and, increasingly, gluten-intolerant individuals make informed food choices. Between 2004 and 2011, the market for gluten-free products grew at an annual rate of 28%. The United States Gluten Free Food Market is forecasted to grow with a CAGR of 10.10% during 2020-2026 period and reach USD 11.4 Billion by 2026.

These programs laid the foundation for the use of certifications in driving new agricultural market growth, and now the regenerative agriculture movement has caught on.

The Emerging Regenerative Certification Landscape

Despite Certified Organic serving as an example of how certifications can drive growth, the system is not perfect and has faced criticism from some farmers and stakeholders for its perceived shortcomings. Among these are that the cost and complexity of meeting regulatory guidelines for organic does not make it viable for small farmers, the potential for fraud – from both foreign crops coming into the U.S. and from scammers within the U.S., and that Certified Organic does not go far enough to create the healthy ecological and economic outcomes for farms and consumers that are expected from the label. Advocates for the Certified Organic label – for which there are many – point out that the label is meant to and will evolve and improve. But as some continue to work to improve the organic label, other new certifications have been developed to better encompass regenerative values that are not necessarily captured by Certified Organic.

Some of these programs, such as Real Organic Project and Regenerative Organic Certified seek to build off of the Certified Organic label – recognizing the positives of the 20 year-old label but wanting to strengthen or move beyond what Certified Organic is today. Regenerative Organic Certification (ROC), which was started in 2017 and may be the most widely recognized of the new regenerative labels, claims to use Certified Organic as a baseline and then integrates with other existing animal welfare and social fairness standards bodies.

Other programs – such as Land to Market’s Ecological Outcomes Verification (EOV) – take an entirely different approach and instead of dictating practices used, measure outcomes. EOV contextualizes evaluation and assesses key indicators of the health of the ecosystem, such as soil health and biodiversity, to the ecoregion in which the farm or ranch belongs.

The newest verification program to join the mix, Regenified, was started by the team at Understanding Ag, including regenerative farming pioneer Gabe Brown. Gabe recently explained that the only way to get meaningful movement from convention toward regeneration is to provide a framework that is as inclusive as possible on the front end. To accomplish this, the program is designed to be inclusive of any farmer no matter where they are on their journey to regeneration.

Want to know more about the different certification programs? We’ve put together a cheat sheet for regenerative certification and verification programs here.

Help or Hindrance for Farmers

The goal of all certification programs is to better define regenerative, help farmers and companies differentiate themselves by their regenerative nature, and drive growth. But with so many new certification programs, it’s hard to say whether they will ultimately be a help or a hindrance to the development of the regenerative market.

“We see certifications as helping to increase the number of acres under regenerative ag practices – increasing soil health and that of the planet overall,” says Blake Alexandre. The farm that he and his wife (and now their kids) run in northern California has been deemed America’s first Regenerative Dairy and holds not only Organic and Regenerative Organic Certifications but also Land to Market’s Verification, among other certifications like Certified Humane. Both ROC and Land to Market offered the farmers a chance to get certified – formally recognized – for practices they were already implementing on their farm.

“We are big fans of Allan Savory and his holistic management mindset, so wanting to be a part of Savory’s regenerative certification was a natural fit,” explains Blake. In 2018, Alexandre Family Farms was also chosen as one of 19 farms worldwide in ROC’s pilot program and they launched their first ROC product in 2020. But while the Alexandres have embraced certifications and used them to drive business, not all farmers share their enthusiasm.

Saskatchewan grain farmer Derek Axten of Axten Farms has his sights set on producing high quality grains and other foods and thinks practice-based certifications won’t get us there. He explains that in his view, “a checklist of what not to do will only get you so far, there will always be a significant amount of producers who ride the minimum train as long as possible.” In lieu of certification, he believes in outcomes-based measures and has been testing nutritional content of their grains, as well as glyphosate and AMPA residues, for the past four years with Dr. Jill Clapperton. “We need to pay food producers on the outcomes, the rest will look after itself. I’m not sure how a certification can enable growers any better than that?”

Despite these different views on certification, both Derek and the Alexandres are cautious about the implications of so many new certifications programs for regenerative. Axten explains that he’s concerned that “the increasing number of certifications will only further muddy the already confusing waters in the space of regenerative ingredients for both the farmers and the consumers.”

Blake agrees. “This is good and bad for the farmers, and bad for consumers. It’s good that farmers have more options to choose a certification process that can bring more, and loyal, values-based consumers to their products, but too many certifications, especially at this early awareness stage of regenerative ag, will hamper consumer’s ability to easily recognize or be loyal to or feel confident in the certifications.”

What Role Do Certifications Play in Investment?

Similar to the way that certifications play a different role for each farmer, investors are also approaching certifications from varied perspectives.

On the one side, Certified Organic has proven itself as a valuable lever for some investors seeking to gain value on investments in farms and farmland. Two pioneers in regenerative farmland investing – SLM Partners and Iroquois Valley Farmland REIT – are among a larger group of investors that incorporate Certified Organic into their strategy. Iroquois Valley – an organic farmland finance company that provides farmer-friendly leases and mortgages – requires that farmers certify their land organically or begin the transition to organic as a result of Iroquois Valley’s investment. The company chose Organic as their standard because it is the only national legally enforceable certification. SVP of Investor Relations Donna Holmes says that the certification also fits well with Iroquois Valley’s works to improve the triple bottom line – economic, environment, and social benefits.

“Organic certification satisfies all three criteria.” Donna explains that, “it allows farmers to access higher price points for their products, which makes a difference in their cash flow and profitability; it serves the environment by eliminating toxic synthetic pesticides and promotes crop diversity; and socially it allows historically underserved producers a way to enter farming and food production.”

Echoing Derek and the Alexandres, Donna expressed some concern about the influx of new regenerative labels, highlighting again the confusion in the market for consumers and investors. “The lack of clear definition for regenerative is adding to that confusion, even as it contributes to growing awareness around these concepts,” she told us. “We all lose when we let a subjectively defined buzzword lead the way because it can erode trust in hard-fought certifications.”

Stephen Hohenrieder, founder of Grounded Capital Partners, thinks about certifications a little differently. Grounded Capital invests in established companies where they see an opportunity to align high-integrity supply chains and create more demand for regeneratively-produced ingredients. The foundation of their thesis is that regenerative food systems depend on authentic, traceable and transparent connections between consumers and the source of their food. Stephen explains that they support all efforts to “build awareness and capacity for more transparent and traceable production of food,” but believe that certifications will play a decreasing role in this. He says that “consumers are relying less on third party certification as their seal of approval and are increasingly establishing relationships with brands that they relate to and trust.”

The increasing number of regenerative certifications coming online seems to be a natural progression as the regenerative space develops and as different parties establish their definitions of regenerative, according to Stephen. He expressed hope that the certifications that are ultimately adopted will be that much better off as a result of this more competitive dynamic.

What’s Next?

The regenerative food system is in its infancy and there are many stakeholders – from farmers and brands to certifiers and investors – working to simultaneously define it and grow it. These two objectives will develop hand-in-hand and certifications will play a role. To find success, however, these programs will need to show proof of concept by gaining farmer adoption and, says Patrick Smith of regenerative venture studio Wolf Tree Venture, win the supply chain. He explains that many large brands need 3rd-party certifications in order to make product and process claims, and currently only ROC and the Soil Carbon Initiative meet that bar, while several others rely on 2nd-party verifications. It will be details like this – that test these programs’ ability to move from paper to practice – that will ultimately help determine the market viability of any given certification program. Blake Alexandre adds, “Certified regenerative seals will need to have amplification of the value of the seal from all the stakeholders in the conversation.” Those programs that can accomplish this will rise to the top and ultimately help scale regenerative food systems.

This is a robust and hotly debated topic – we want to know what you think. Send us your thoughts and questions here.

Sarah Day Levesque is Managing Director at RFSI & Editor of Raising Regenerative News. She can be reached here.