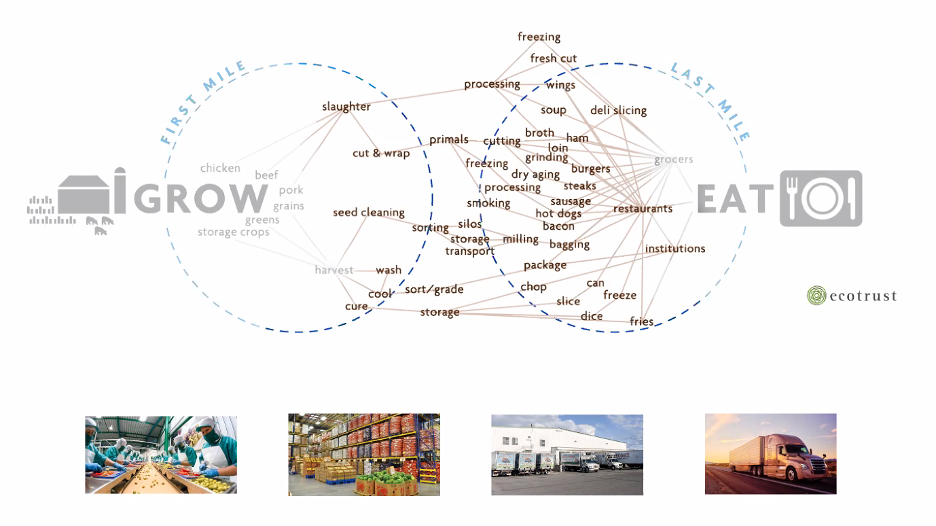

Despite billions of investment dollars flowing into agriculture today, very little goes into regenerative systems. Even though awareness of regenerative agriculture is increasing and capital investment into it is rising, there is a large deficit in investment in the middle the food system: the processing and distribution infrastructure that helps get regenerative products from the farm to retailers and consumers. This article is an edited transcription of Tim Crosby’s talk from the Regenerative Food Systems Investment (RFSI) Virtual Series focusing on opportunities to invest in this “invisible middle” of food systems.

The “invisible middle” of agriculture — or the “messy middle,” as some call it — includes the processing, distribution and storage parts of our food system. It’s everything between the farm and the plate.

Most consumers don’t know much about this vital space, but I look at it as equivalent to the plumbing or electrical wiring of a house. You know it’s there, but you don’t worry about it as long as it works. But when it doesn’t work, everything falls apart.

The demand for sustainable and organic products is in growing demand — not just in smaller, direct-to-consumer markets, but also in mid-sized and large buyers. How do we get regeneratively grown products to market when the processing is invisible and its importance is not understood? There’s a pressing need for more people to recognize this issue.

I’d like to frame this conversation in terms of the principles of risk and return, efficiency and scale.

Risk

We don’t need to spend much time discussing what we all lived through in the last two years with COVID. Our global supply chains broke down, and they still haven’t fully recovered. We had shortages — most visibly in meat processing capabilities. There were extreme pressures on food banks. Food production has moved into a global marketplace, and, as the pandemic demonstrated, we don’t have the redundancy built into the system to keep things going when the system breaks down.

But there’s a silver lining: the pandemic did get the attention of the federal government to change things around. USDA is already working to invest a billion dollars to reduce the concentration in meat processing among the four largest companies. This is something that USDA has been working on for several years, but they didn’t have much luck until COVID demonstrated the need to change direction. And government’s work here is critical: a trillion dollars in global agriculture subsidies go out annually, but only about 1 percent goes toward supporting regenerative systems. When we get a billion, that means there’s $999 billion going elsewhere, in essence. We need policy incentives to really move the needle.

Return

Can we learn how to better assign risk in regenerative investment decisions so that the borrowing rate will start to move lower? These impact-oriented businesses do more than return money. As an example, I’m an investor in Organically Grown Company, the largest organic distributor on the West Coast. OGC pivoted during COVID to help the food in their supply chain get to local markets. Beyond this social return of fresh produce donated to food banks, OGC annually tracks amount of food waste diverted to livestock feed, amount of food sourced from and benefiting regional economies, percentage of organic products sourced and distributed, and amount of profit donated to non-profits. This is not the norm for wholesale distributors, but this company is very grounded in its community. Aren’t returns like these worthy of more investments?

In the impact-investing space. investors are looking for both financial and non-financial returns. One of the tough things in the ag sector is that the financial returns are generally lower than other sectors like tech. This reduces the interest for a traditional investor to invest in this space, including those who require a market rate return before considering the impact returns. Plus, most investors don’t understand regenerative agriculture because there are not yet enough examples, enough precedent, to show actuaries and investment committees how to uniformly understand the risk and returns of regen ag companies involved with processing and distribution. Examples like OGC highlight the environmental, social and human returns alongside the financial returns.

Efficiency

There are also issues with efficiency in the invisible middle. One great example of this came to me from Eddie Mukiibi, Vice President of Slow Food International. He told me a story about a $20 million processing center recently built in Uganda for heirloom mangos.

To show how the factory operated on day one, though, they had to use imported mangos. Why use imported mangos for an heirloom mango processing facility? Because the processing equipment was built for uniform sizes of mangos. It was designed for efficiency of throughput and yield, or how many units per minute it can process. But heirloom is anything but uniform in size, so the machinery could not handle the variability of their local product.

This for me really highlights how we have to revisit the definition of efficiency. If our goal is to maximize yield per acre or units per minute or hour, we have to have product of a uniform size going through that machinery so we can hit those numbers. But if our goal includes heirloom, biodiversity, culture, taste, quality, etc. — then the definition of efficiency has to move from a maximization strategy to an optimization strategy where throughput or yield is only one of a handful of considerations.

We have to re-examine what we mean when we talk about efficient processing infrastructure. We have to be open to the fact that the equipment will probably cost more right now — although it hopefully won’t in the future. This may be particularly difficult here in the U.S., where manufacturers typically build processing systems for large-scale businesses. Many on-farm or small- to mid-scale processors I work with procure machinery from developing nations because it isn’t made in the U.S. anymore. Optimized-scale processors need equipment that’s not maximized for efficiency on throughput alone.

Scale

The regional, organic, sustainable food movement took off in the 1990s with the growth of farmers markets and community supported agriculture programs. The number of farmers markets in the U.S. grew from fewer than 2,000 in the mid-’90s to over 8,000 by 2015. People were getting food that connects them with farms and that generate stronger community relationships. They starting seeing products that are not from a maximization strategy; they are instead from an optimization strategy.

But consumers don’t want to just shop on Saturday morning; they want that quality of food at their grocery stores all week long. This puts pressure on larger retail establishments, and even some institutional buyers, to answer these customers’ wishes. By 2015 Costco began helping organic farmers buy land to grow organic chicken. General Mills developed a non-GMO Cheerios. Kroger started advertising local-grown products. Large players recognized the need to start producing larger quantities of these types of products. Today the largest sellers of organic products are Costco and Walmart.

Investing in the Middle

The market pressure is now on regional scale identity-preserved food that is aligned with the values and goals of smaller, direct markets but compete on price in the wholesale markets. How can we improve this middle space for regenerative growers and consumers? I work at the intersection of food, finance and philanthropy. I try to use whatever capital is necessary to advance the issue of processing capacity for regenerative systems, which I believe is critical.

If the goal and mission of investments were to open markets, then maybe taking a loss to open up a market could be a way to do it. I wouldn’t recommend that for everybody, but it depends on the goal of your investments. With a philanthropic lens, every investment can be a 100 percent loss. Maybe it’s minus 50 or minus 10 percent — but the goal is to open up markets.

Two different investments I was a part of in this space have done this. One was scaling up organic, grassfed beef in the Northwest; the other was in the production of fair-trade, organic, greenhouse peppers and cucumbers in Mexico for the U.S. market. Both succeeded in opening their respective markets, but the companies themselves got squeezed out.

As an investor, a really interesting aspect of this — especially on an individual basis — is that an investment loss is more valuable on a tax return than a charitable deduction. It comes down to how investors think about properly placing concessionary money.

Separately, I was asked by Mission Driven Finance to help set up a fund focusing on investing in processing for regenerative systems, and I’m now an investor in the fund. One example of an investment we made that’s really helping regenerative farms is Cairnspring Mills in northwest Washington. Kevin Morse, Cairnspring’s founder, is a farmer and had worked at the Nature Conservancy, and he saw that farms in the region were growing grain as part of their rotation with potatoes to rebalance nutrients and pests, but they weren’t profiting from the grain since there was no buyer. By starting the mill, he helped farmers stabilize their income; they were able to open up and diversify their revenue channels by making money on the grain. They couldn’t have done that without somebody there to accept smaller-volume orders coming into the mill.

As Cairnspring Mills grew, it realized it needed to secure the harvest from the farmers. This is a specialty crop — as most are in this space — and as a processor, you can’t just turn to a commodity silo or a feedlot. What really helps a mill like Cairnspring is to buy the harvest at the beginning of the season so they know they have inventory at harvest time — and that requires a financing vehicle that essentially works with the cycles of nature.

To help with situations like this, Mission Driven Finance has developed a harvest note. The financial disclosure for the note makes clear that the goal is to support the shift to regenerative agriculture. This isn’t just to make money. This is also about helping regenerate soil, help producers, help the environment and help marginalized rural communities.

Uniquely, the fund is structured around a three-year commitment for investors who choose their return — anywhere between 0 and 7 percent. This is an innovative step; to ask investors what rate they need. For the first note, the business secured a loan of just over 6 percent. So there is interest among investors to not simply maximize financial return if they know it’s doing something important.

The other beautiful thing with this investment is that by providing working capital, Cairnspring Mills can then offer a purchase order or contract to the producer at the beginning of the season. This means that the producer has collateral they can use for their working capital needs, which can reduce their own borrowing rate. And it has played out that way. By working in the processing space, you’re not just helping product flow — you are helping secure and stabilize revenue for regenerative farmers. This part of the food system is not well understood. But when you start working on the plumbing in the walls, you start to help the whole system function properly.

Tim is the principal director of the Thread Fund, which focuses on investing multiple forms of capital to generate social, environmental and financial returns. He has many years of experience investing in and funding regenerative food systems. He is a steering committee member of the Global Alliance for the Future of Food, a member of Agroecology Fund, chair of transformational investing in Food Systems Initiative, a member of the Seattle impact investing group and a board member of the Center for Inclusive Entrepreneurship. Most recently, Tim has worked on developing the Regenerative Harvest Fund with Mission Driven Finance, which aims to fix the bottlenecks in our food system that limit processors’ and producers’ ability to achieve scale.